Helping the Haathis

Working with modern communication systems and animal behaviourists, Ruth Ganesh, Trustee of the NGO Elephant Family, tells us how we can protect the beloved pachyderm from decimation in Asia

Whenever I left for a long journey across the seven seas, my grandmother insisted I ate a spoonful of yogurt with sugar and uttered “Jai Ganesh” under my breath. Not one for rituals, I yet followed her instructions meekly. The elephant headed god, the son of Shiva and Parvati, the remover of obstacles, is dearly beloved. Lord Ganesha is the most worshipped deity in the Hindu Pantheon. His earthly brethren, however, the elephant, is under threat. In the past century, the population of the Asian elephant has plummeted by 90 percent as its habitat shrinks, leading to an increase in man-elephant conflict, with poaching continuing unabated.

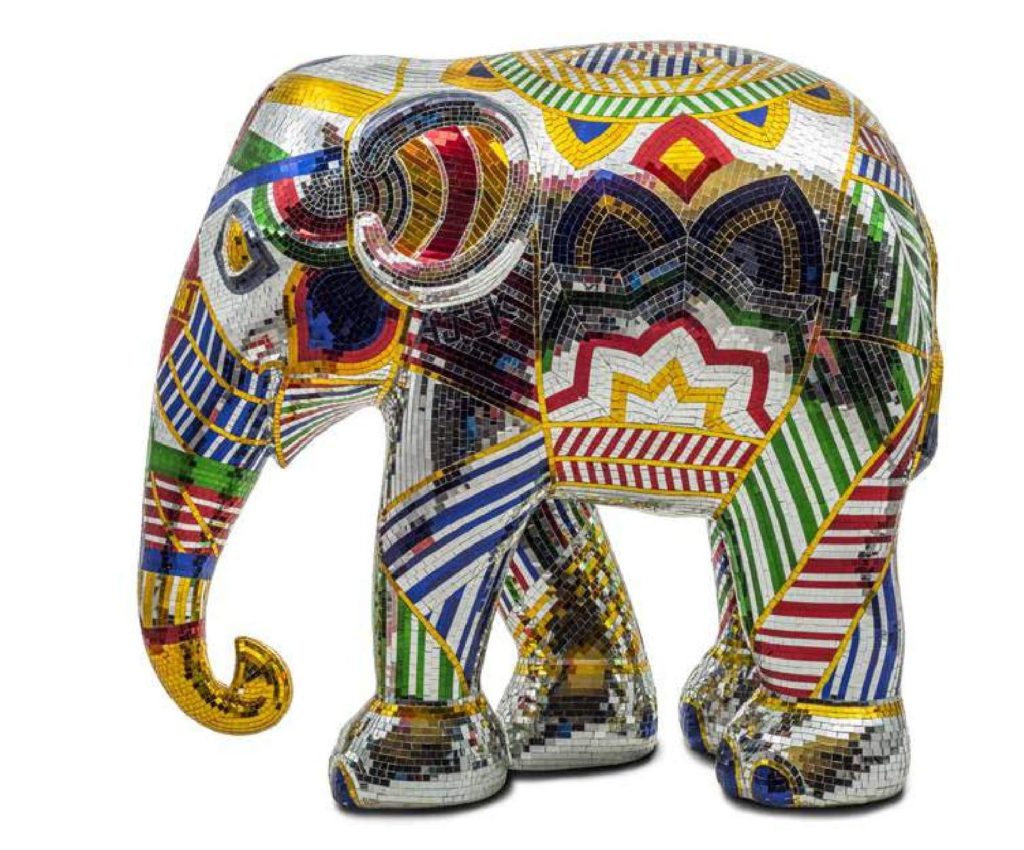

The Elephant Family, an International NGO committed to protecting the Asian elephant from extinction in the wild, has funded over 160 projects since its inception in 2002. A part of its effort is the Elephant Parade, the world’s largest art exhibition of decorated elephant statues. The Indian edition had Rohit Bal, Amitabh Bachchan, Sabyasachi Mukherjee, and a host of other artists create 101 pachyderms that eventually went under the hammer, the funds going to create elephant corridors in the country and rescue centres around the forests. (Beej Edit note: Elephant corridors are narrow strips of land that allow elephants to move from one protected park and habitat to another. In these narrow, unprotected corridors elephants and other animals are generally vulnerable.) Out of the 101, 73 so far were sold all within India raising Rs 5.75 crore in this event’s first edition.

Ruth Ganesh, trustee, Elephant Family says we need to understand and protect our wild landscapes and our forests and all the rich interconnected biodiversity they support, especially, of course, elephants

“Elephants are the architects of forests and forests are vital to us all,” says Ganesh, having wrapped up this auction successfully. “We depend on forests for our survival, from the air we breathe to the wood we use. Besides providing habitats for animals and livelihoods for humans, forests also offer watershed protection, prevent soil erosion and mitigate climate change.”

For all of us feeling bereft with the delightful tuskers having gone to their homes, Ganesh has some good news. “There is a team of 70 brilliant creatives working in Mudumulai in South India building a herd of 100 life-size elephants out of steel and lantana, which will go live at the Kochi Biennale at the end of this year,” reveals Ganesh. It’s a long wait till these pachyderms go ambling across the country, till then; Ganesh speaks the legacy we need to leave for the next generation.

What drew you to pachyderms, inspiring you to work for their conservation, rather than any other species?

I grew up with a love of epic landscapes and faraway places. It wasn’t so much specifically the elephant, but more the forests they lived in that attracted me. That and having a meaningful adventure in life. To me, just looking at an elephant is living, breathing adventure. The elephant has got to be one of the most curious animals ever to walk this earth, and to lose the elephant would really be like losing our own imagination.

It’s time to celebrate with the haathis!

Tell us about your work in India thus far?

Elephant Family’s Founding Leader Mark Shand rescued an elephant begging in the streets of India and this prompted him to found the NGO. Our work has focussed on India—teaming up with the most pioneering organisations here to mitigate human elephant conflict and protect India’s forests. We have been active here for 15 years, but never applied our ambitious awareness and fundraising strategies. Changing this was the biggest challenge and equally the biggest opportunity.

India is a sort of conservation miracle with 27,000 elephants remaining, compared with 200 in China, a country of the same population. Achieving public and political support for this endangered species is key to saving it from extinction. Events like Elephant Parade are a catalyst.

What were the biggest challenges in executing this project?

There is a phenomenal amount of behind-the-scenes preparatory work. Having done this for 10 years, we can still never fully predict the details. Everything starts from scratch in a new city—production, logistics, permissions, artwork, and marketing—all have to be tailored and it’s thanks to the generous political support and expert organisations we’ve been working with here for the last 18 months that this exhibition made it to the streets in such spectacular style. We knew India was a great centre of creativity and expected this to be a huge success for this heritage animal and were not disappointed.

We are forever grateful to every single one of the artists, and to the phenomenal curators of the exhibition—Farah Siddiqui and Aqdas Tatli— for lending their wealth of talents to our cause. The response from the artistic community has been heart-warming and exciting.

Interior designer Vikram Goyal’s Savitri made out of brass with lattice work commanded a jumbo Rs 18 lakh

Were you surprised by the response the elephants received?

Everybody loves elephants, even if they haven’t met one in person! We had hoped for an enthusiastic response, but what we actually experienced was more than just enthusiasm. The parade helped create meaningful friendships with a number of companies and individual philanthropists we believe we’ll carry forever and will be at the frontline of our work in the most meaningful way. The most joyful and happy surprise was to see just how much the message resonated in India, which was very different to other countries where this exhibition has been put on. Everybody had their own elephant stories as well as their parents and grandparent’s tales. The concept of the elephant corridors seemed to be well understood, it was a marvellous sight to see a child who was no more than eight year’s old explaining corridors to their mother. Often this doesn’t stick but we hope these elephants will help change that.

Post the auction, what specific areas will the funds be invested in and how will it be monitored?

All of the funds raised from the event will be invested in elephant conservation in India, supporting key conservation projects throughout the elephant’s habitat, from Kerala in the south to Assam in North-East India. Fifty percent of the total funds have been specifically earmarked to help secure the next of the 101 elephant corridors that have been identified by The Asian Elephant Alliance—a partnership of Wildlife Trust of India, Elephant Family, The World Land Trust, IFAW and IUCN. These vital corridors, or passages, link one elephant feeding ground to another and form the elephant’s traditional migratory routes. Over the years, these corridors have been blocked or fragmented by human development including settlements, farms, railways and roads bringing humans and elephants into conflict for food and space. Securing these corridors for wildlife will help reduce conflict and provide safe landscapes for elephants and people alike.

HH Maharaja Sawai Padmanabh Singh of Jaipur’ elephant painted by Ramu Ramdev and team of the beauty surrounding Amer Fort

One of the first corridors secured was the Tirunelli-Kudrakote elephant corridor in Kerala which received legal protection in 2015, meaning that elephants will be protected in perpetuity. However, Elephant Family still funds the monitoring and evaluation of this conservation success to ensure that best practices are maintained and that a sustainable, conservation model is in place as we develop and secure new corridors across India.

Some of the other conservation projects funded by the event include human-elephant conflict management in the foothills of the Karbi Hills in Assam and managing the invasive weed Lantana Camara in wildlife landscapes in Tamil Nadu. (You can read in detail about their projects here)

Designer Rahul Misra with his elephant

What was interesting was the access that people had to the elephants. People could hug, touch and take pictures with them. Do you feel such interactions led to a shift in perception about elephant conservation in the minds of people?

This was entirely deliberate—ensuring the artwork and the message is accessible to the man on the street is important. One of Mark’s favourite sayings about how to fundraise is ‘make people smile and then ask them for help’ and we remain true to that philosophy with our events. Our aim is to highlight a serious message in the most colourful way that delights rather than depresses people—Elephant Parade does just that.

Is there any timeline for the implementation of these projects? What would be the measure of success?

Our goal is ambitious— to secure 101 elephant corridors by 2025. By securing them we aim to restore the wildlife corridors that link traditional feeding grounds enabling elephants to move safely, free from the interference of people. As in the Kerala example, relocation of settlements out of the corridors is sometimes necessary. Happily, the 37 families that voluntarily relocated in Kerala are extremely happy with their new homes and the land they farm free from passing elephants. It’s a win-win situation for elephants and people.

Designer duo Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla’s blingy tusker

There are many instances of man-elephant conflict in India. For instance, I recently visited Coorg and a few coffee plantations have electric fences to keep tuskers away. How do we minimise conflicts in a humane manner?

Much of the conflict arises when elephants raid crops and food from houses and people naturally defend their property. There are a number of deterrents that can be used— elephant trenches and bees are examples, but elephants are intelligent and a hungry elephant will often work out a way to by-pass these! We are currently funding an animal behaviourist to try to understand the key triggers that make an elephant a crop-raider, so that we can create more effective deterrents.

Evidence has shown, time and again, that violence and noisy protests against elephants can make the animals more violent, not just at the point of conflict but in future situations too. We also fund community-based early warning systems, which send SMS messages to phones, which notify villagers when there are elephants in the area so that they can avoid stepping into conflict situations.

Leaving a legacy behind for the future

As citizens of this planet, what legacy can we leave for the next generation?

We should help engender respect for wild spaces by understanding how they, and the animals that live in them, are vital for our own survival.

For three millennia elephants have moved through the forests of Asia, forging passages through the landscape to connect one feeding ground to the next. Their perpetual processions clear old vegetation, make space for new growth and allow sunlight to dapple the forest floors to fuel new life. They disperse the seeds of the plants they eat through their dung, seeding and composting as they go, nourishing countless plants and insects on which a hundred other species depend; the herbivores and, in turn, the carnivores that feed upon them. They are the architects of our forests. If there is a single legacy that we leave, it should be to understand and protect our wild landscapes and our forests and all the rich interconnected biodiversity they support, especially, of course, elephants

We’re excited about the new herd. When do we see them?

The 100-strong herd made of steel and Lantana will go live at the Kochi Biennale at the end of this year. We then hope to bring them to another major Indian city before they go on tour to the UK and America too. With their strong conservation message to put India’s elephants on the map, just like Africa’s elephants, we believe that this is only the beginning of our elephant revolution!

To know more about the projects and how you can donate or contribute to their efforts, visit their website. All images courtesy from the Elephant Family.

Most Read Articles

A Complete Guide to Demi-Couture Jewellery in India

The ultimate guide to artistic baubles and demi-couture jewellery that evokes the splendor of India... Read More»

Rajasthan’s Aangi Finds New Life in Aangiwali’s Fusion of Tradition and Style

Aangi is a garment woven with history. In the arid landscape of Shekhawati, Rajasthan, it... Read More»

The Ultimate Guide to the Best Natural Deodorants in India

The top 12 natural deodorants that banish BO and nix nasties for round-the-clock freshness Our... Read More»

Easy Yoga Practices for Menopause Relief

Dr Hansaji Yogendra, Director of The Yoga Institute and President of the Indian Yoga Association... Read More»